Lit Hub is pleased to present the latest installment in a new series from Poets.org called « enjambments, » a monthly interview series featuring both new and established poets. This month, the spotlight is on Samantha Rose Hill and Genese Grill.

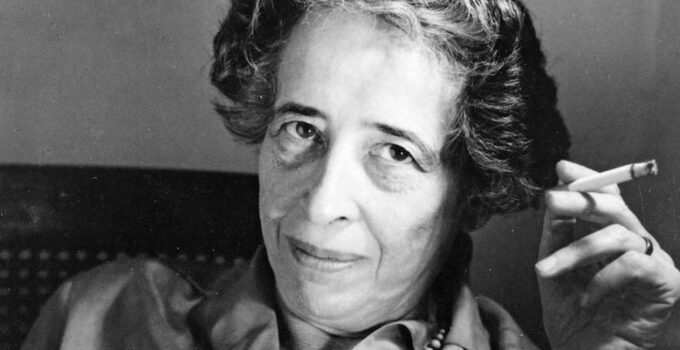

Samantha Rose Hill is the editor and translator of « What Remains: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt » (Liveright Publishing, 2024) and the author of the biography « Hannah Arendt » (Reaktion Books, 2021). She is currently working on her upcoming book, « Loneliness, » for Yale University Press. Hill is a visiting scholar at the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing at Wolfson College, University of Oxford, and associate faculty at the Brooklyn Institute for Social Research.

Genese Grill is a translator and scholar of Germanic literature. She collaborated with Hill on editing and translating « What Remains: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt » and has authored several books, including « The World as Metaphor in Robert Musil’s The Man Without Qualities: Possibility as Reality » (Camden House, 2012). Grill, who has translated four books by Musil, is currently working on the first English-language biography of the author for Yale University Press.

In a recent interview with Poets.org, Grill and Hill discuss their translation project and the significance of poetry in Hannah Arendt’s life. Arendt viewed poetry as a way of thinking that reflected her philosophical openness, engaging with metaphor, sound, and rhythm as essential components of aesthetic-ethical expression. While Arendt’s poems may not have been intended as historical chronicles, they offer a personal exploration of ideas, emotions, and experiences that resonate with readers across generations.

Hill emphasizes that Arendt’s poems are dialogical and conversational, reflecting her unique approach to language and storytelling. The poems in « What Remains » are arranged chronologically, providing insights into Arendt’s personal and intellectual evolution, particularly during her years of exile. While the poems capture the challenges of war, exile, and personal relationships, they also speak to timeless themes of love, cruelty, and the search for belonging.

Ultimately, the poems in « What Remains » serve as a testament to Arendt’s commitment to communication and understanding, transcending time and space to bridge differences and complexities. Through their translation and analysis, Grill and Hill offer readers a deeper appreciation of Arendt’s poetic legacy. Organizing them thematically would have required creating a book in Arendt’s name that she never actually wrote. She never compiled a collection of poems during her lifetime, instead leaving her poems scattered in archives around the world. Arendt anticipated that her poems would eventually be discovered, much like how she discovered Rahel Varnhagen’s letters in the Prussian State Archives before being forced to flee Germany in 1933 due to persecution by the Gestapo.

Arendt’s writings reflect a consistent mood of melancholy, introspection, sentimentality, and romance. She possessed a deep love for life and a strong desire to comprehend it. Writing was her way of making sense of the world, engaging in inner dialogues with herself while reclining on her sofa. When inspiration struck, she would jot down her thoughts in a notebook or on a typewriter, offering readers a glimpse into her thought process through her poems.

For Arendt, the process of going out into the world and then retreating to solitude to reflect and narrate one’s experiences was crucial. She believed in transforming internal impressions into tangible language that could be shared with others. Poems, in her view, represented the most concentrated form of language, bridging the gap between the private realm of the mind and the public sphere of expression.

Translating Arendt’s poems presented numerous challenges, as capturing the nuances of her German verses in English was a complex task. The translators strived to strike a balance between form and content, often sacrificing literal accuracy to convey the intended meaning and emotion. Each word and line was carefully considered, drawing on Sam’s extensive knowledge of Arendt’s life and work to guide their choices.

Maintaining the en face format, with the original German text alongside the English translations, was a deliberate decision to honor the inherent untranslatability of Arendt’s poems. The translators respected the poems in their raw, unedited form, preserving Arendt’s stylistic choices and underlined words like « is » and « us » as she had originally penned them.

In cases where multiple versions of a poem existed, the translators opted to publish the final edited version to offer readers a glimpse into Arendt’s evolving creative process. The goal was to present the poems as authentically as possible, staying true to Arendt’s original intent and leaving them unaltered in their most final state. Découvrez ce que deux poètes lisent en ce moment!

Plongée dans la lecture

Dans quelques cas où il y avait quelques versions avec des différences substantielles, le texte original a été inclus en note de bas de page ou en note de fin. L’objectif était de rester aussi fidèle que possible au texte d’Arendt.

Lorsqu’on a demandé à GG ce qu’il lisait actuellement, il a mentionné le livre de Dagmar Barnouw intitulé « Weimar Intellectuals and the Threat of Modernity ». Ce livre explore le danger des idéologies politiques rigides dans les années précédant l’ère totalitaire, soulignant l’importance d’un domaine d’ouverture esthétique et éthique pour la liberté créative et politique. Il est également plongé dans les lettres de Robert Musil de l’année 1938, qui racontent sa fuite d’Autriche avec sa femme juive après l’Anschluss avec l’Allemagne. Ces lectures résonnent avec le travail poétique et philosophique d’Arendt.

SRH, quant à elle, jongle entre plusieurs lectures en ce moment. Elle participe à un groupe de lecture sur « La Montagne magique » de Thomas Mann, et pour son plaisir personnel, elle se plonge dans « Jane Eyre », « Pilgrim at Tinker Creek » d’Annie Dillard, et « Mina’s Matchbox » de Yōko Ogawa. Elle lit également un long rapport de l’Organisation mondiale de la santé pour le livre qu’elle écrit sur la solitude.

Poésie préférée

GG a partagé ses poèmes préférés sur Poets.org, incluant « To His Coy Mistress » d’Andrew Marvell, « One Need Not be a Chamber — to be Haunted » d’Emily Dickinson, et « [since feeling is first] » d’e.e. cummings. SRH a également partagé ses favoris, comme « Otherwise » de Jane Kenyon et « The Lake Isle of Innisfree » de William Butler Yeats.

En bonus, Poets.org propose une série d’interviews mensuelles intitulée « enjambments », mettant en lumière un poète émergent ou établi ayant récemment publié un recueil de poésie. Chaque interview est accompagnée de poèmes du recueil du poète et d’une lecture par ce dernier, à découvrir sur Poets.org et dans la newsletter hebdomadaire de l’Académie des poètes américains.